The Railway Children* by Edith Nesbit was first published as a book in 1906, having been serialized in The London Magazine the previous year. The story revolves around three children, Roberta (Bobbie), Phyllis and Peter. When their father leaves home without the children knowing why, they, with their mother, move from their large townhouse near London to a cottage in the countryside. The absence of the father is one of the grand themes of the story. It is apparent that the mother knows why he has gone, but she does not tell the children and Nesbit does not in the meantime reveal it to the reader. Roberta, the eldest, eventually finds out the ‘terrible secret’ and the reader then has the secret revealed through her eyes.

The opening paragraph of the book describes in detail the luxuries of their suburban home, summed up as having, “every modern convenience” (p. 1). This sets up the contrast with the cottage which has to be lit by candles when they first arrive and, according to the ‘cart man’ who brought them from the station, is infested with rats. However, the contrast with the suburban home is offset by Nesbit having the family view their surroundings in an optimistic and cheerful way. So Chapter Two begins, “‘What fun!’ said Mother, in the dark, feeling for the matches on the table. ‘How frightened the poor mice were - I don’t believe they were rats at all’” (p. 22). The next morning, the children have to wash outside using a pump in the yard. This ordinarily would seem a hardship compared with a suburban home, but the children see it in its best light: ‘“It’s much more fun than basin washing,’ said Roberta. ‘How sparkly the weeds are between the stones, the moss on the roof - oh, and the flowers!’” (p. 28). The apparent beauty of the immediate environs of the house also extends to the surrounding countryside. So the approach to the railway line, across what is unpromising scrubby and rocky terrain, is likened to the decoration on a cake: “The way to the railway was all downhill over smooth short turf with here and there furze bushes and grey and yellow rocks sticking out like candied peel from the top of a cake” (p. 32). The reality is that the family have come to a tough environment in an equally tough financial situation; Peter at one point resorts to stealing coal to help the family. However, the idealized, romantic, description of their surroundings is an important element of the story. But at the heart of the book is, of course, the railway.

Whilst still in their suburban home, Peter is given a working, toy steam engine for his birthday. Nesbit uses this as a device to show the children’s attitude to trains. The train is Peter’s favourite present and, after the engine breaks down and the father is discussing with the children how he would repair it, Roberta states that she would love to be an engine-driver, or even a fireman. Although Phyllis is not so keen on this idea, the reader is left in no doubt that the children love the railways.

The romantic description of the countryside is more than matched by Nesbit in her portrayal of the railway. As the children walk along the line, “the very sleepers on which the rails lay were a delightful path,” and when they walked into the station, “by the sloping end of the platform. This is in itself was joy” (p. 34). The station is described with religious overtones, for she refers to the Station Master’s office as the “sacred inner temple behind the place where the hole is that they sell you tickets through …” (p. 56). Nesbit uses the language of joy and sacredness to capture the childlike wonder which the children had of the railways. And she takes every opportunity to evoke the atmosphere of railway stations at the beginning of the twentieth century, sometimes using detailed description. For example, in the waiting room were framed advertisements of “Cooks’s Tours and the Beauties of Devon and the Paris - Lyons Railway” (p. 136).

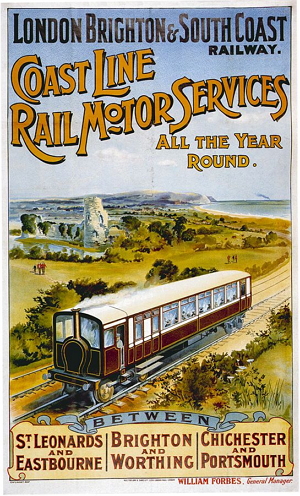

1906 Railway Poster **

These descriptions are perhaps even more powerful in the imagination for readers today because they bring to mind the later railway posters of the 1920’s with their distinctive Art Deco style, the continuing popularity of which is evidenced by, for instance, their use today on retro-calendars.

The railway also provides a cue to fire the imagination of the children. For example, they liken a train to “a great dragon” (p. 32) and the sleepers were “stepping-stones in a game of foaming torrents” (p. 34). Eventually the trains become personified in the imaginations of the children. In the days after the children had stopped the train from hitting a landslide, Bobbie would have nightmares about “the poor, dear trustful engine … thinking that it was doing its swift duty” (p. 130). Added to this was the human side of the railway, for, “everyone on the railway had been kind to them - the Station Master, the Porter, and the old gentleman who waved” (p. 74). Of these, Perks, the friendly but proud porter, figures the most prominently with regard to interaction with the children, particularly in the chapter concerning his reaction to the gifts given to him on his birthday. But it is the old gentleman who is pivotal to the outworking of the plot, and who enables the railway line to function as a communication channel much like the internet today.

The railway line plays a key role in the plot of the story and it is helpful to compare it with the role of the modern internet. In particular, of central importance is the role of one of its regular passengers, the old gentleman. He is seen each day on the train to London and the children notice him waving back when they wave at the train. When their mother becomes ill, the children determine to give the old gentleman a letter requesting that he obtain the necessary medicines, on the basis they will pay him back when they are able. The process by which this is carried out involved Peter and Roberta displaying a message, “LOOK OUT AT THE STATION” (p. 64). When the train arrives at the station the old gentleman is duly alert and Phyllis runs after the train and delivers him the message. This is roughly similar to an email being sent and the computer giving an alert when it arrives. The same day, a hamper is sent to the cottage containing the medicines and much more besides. This is internet shopping at its best! The next significant contact is when the children ask him to help find the wife and child of the Russian author, Mr Szczepansky, who has been given refuge in their cottage. The old gentleman eventually tracks them down, but one can imagine how the internet today might be similarly used to achieve such an end. And, like seeing an online news item, Roberta learns about the reason for her father’s absence from an old newspaper left on the train. And once more she contacts the old gentleman for help.

It should be noted that the contact between the old gentleman and the children is generally mediated by other adults such as the Station Master. Also, when the mother first finds out they had made the contact she admonishes them that they must never ask strangers to give them things. Eventually the old gentleman becomes well-known to both the children and the mother not least because he turns out to be the grandfather of the boy injured in the paper chase.

The analogy with the internet cannot be pushed too far, but it helps to elucidate the communications which take place in the story. What is certain is that, without the link of the line to London, the uploading and downloading of information leading to the end of the story would not have happened.

The story is set in the Edwardian age and less than ten years later the world would be shattered by the First World War. The author, of course, was unaware this would happen, but some of the issues raised in the book become more poignant to the reader with this hindsight. One such issue is the attitude to foreigners displayed in discussions amongst the characters which arise from their dealings with the Russian, Mr Szczepansky. Indeed, it seems this character was based on a real-life Russian, the author, Sergi Stepniak, who, because of his political views, had fled to London where he became friends with Nesbit. It is also thought that the experience of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army who was wrongly convicted of spying for the Germans, provided the basis for the father in the story. Like many classics of children’s literature, the book has roots which run deeper than the simple story.

Nesbit’s brilliance as a writer is no better seen that in the final two pages of the book. I have been careful not to give too many plot spoilers away in this blog, but as Nesbit herself writes just before the end, “Of course you know already exactly what was going to happen” (p. 284). But what sets the ending apart is the way she slowly withdraws the reader from the scene. For example, at one point, instead of, ‘They crossed the field’, she writes, “And now I see them crossing the field” (p. 285). The reader is thus taken a step away from the immediacy of what is happening. The family then enter the house, the doors are closed, but author and reader are left outside. We retrace our steps across the field and then, “we may just take one last look, over our shoulders, at the white house where neither we nor anyone is wanted now” (p. 286). It’s a brilliant ending, leaving the young, and not so young, reader to do some work with their imagination as they contemplate the scene inside the cottage on the hill above the railway line.

* E. Nesbit, The Railway Children, (Vintage Books: London, 2012).

** By paul pod - Flickr: London Brighton & South Coast Railway, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14988699